All-Weather Solar Cells

Never before have the topics of climate protection and renewable energies attracted as much media attention as these days. The rethinking in society begins and drives the energy transition and the development of progressive innovations.

Until now, Chinese scientists have developed solar cells that take advantage of the sun and water to a certain extent, and which generate energy not only from solar power as before, but also from raindrops – and that even at night.

Solar energy is booming and, thanks to technical progress, is becoming more affordable and more effective at the same time.

Their potential is huge given the almost 15 million single-family homes in Germany alone that could generate their own electricity using photovoltaics. More and more owners choose independence from the steadily increasing prices of electricity providers and invest in photovoltaics.

Your energy supplier is the sun. But what if the sun doesn’t shine, the sky is cloudy and it rains? In such cases, battery storage systems secure the supply of self-produced electricity, but their storage capacity will also be used up at some point.

In order not to have to resort to the expensive electricity of the network operators, scientists from China have found a way to generate energy regardless of the weather and the time of day.

The all-weather solar cell produces energy even at night

Chinese researchers led by Prof. Qunwei Tang developed a fascinating solar cell that is excited not only by sunlight, but also by rain drops and generates electricity.

For this purpose, the research team from Ocean University of China (Qingdao) and Yunnan Normal University (Kunming) coated the cell with an ultra-fine, transparent film made of graphene.

The fascinating properties of graphene

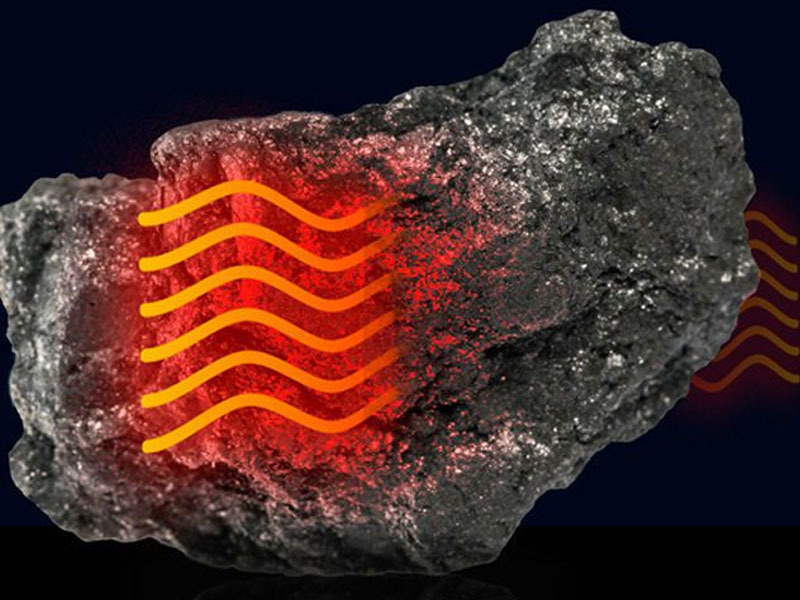

Graphene is a two-dimensional modification of carbon. Among other things, it can be produced by oxidation of graphite (reaction with oxygen), separation of the individual layers and subsequent reduction.

Structurally, each carbon atom in graphene is linked to three other carbon atoms. This creates a honeycomb-shaped, single-layer and therefore wafer-thin pattern with exceptional electrical properties.

For comparison, graphite, one of the most common forms of carbon, consists of several of these layers, which in turn combine to form a three-dimensional grid.

Graphene is extremely rich in freely moving electrons and therefore conducts electrical current very well and, moreover, it is ten times better than copper.

It is more tear-resistant than steel, yet extremely flexible and also transparent. It can be transformed into a semiconductor, magnets and now even a superconductor. His future prospects are unforeseen.

How the all-weather cell works

The solar cell developed in China takes advantage of the electrical properties of graphene to generate electricity from the impact of raindrops. Here’s how it works: Rain is not pure water.

Rather, rain is a solution of water and contains salts, i.e. positively and negatively charged ions. The freely moving electrons in the graphene layer attract the positive ions in the water.

This creates an electrical double layer of electrons and positively charged ions, a so-called pseudo-capacitor. The associated electrical potential difference is sufficient to generate voltage and current flow, even if the current yield is low.

A technical revolution from Kansas

Researchers from the University of Kansas did not want to be content with the sometimes modest electricity yield of the all-weather cell from China and developed a solar cell with a higher output, which is also a few atomic layers thick, and which is also based on graphene.

While her Chinese colleagues covered conventional solar cells with a very thin and transparent layer of graphene, Hui Zhao and his PhD student Samuel Lane from Kansas combined a honeycomb-shaped graphene layer with similarly shaped layers of molybdenum diselenide and tungsten disulfide.

This increases the lifespan of the electrons in the graphene, which stimulates the sun to reach an energy level that is several hundred times higher.

One catch remains: the solar cell only alternately supplies energy from solar and rain. If it rains on a sunny day, the yield does not increase or at least not yet. Still, the new system is light and affordable.